Computational Methods for Magnetism

Anders Bergman, Olle Eriksson, Maryna Pankratova, Manuel Pereiro & Nastaran Salehi, Uppsala University; Anna Delin, Johan Hellsvik, Mariia Mohylna & Qichen Xu, KTH; Danny Thonig, Örebro University

Introduction

Magnetic materials are everywhere. For example, there are several dozen permanent magnets in a modern car and around ten in a smartphone. Decades of research and development of magnetic materials have given us today’s sophisticated electric motors, generators, speedometers, media for data storage, door locks, speakers, microphones, sensors, camera stabilisation, and wireless charging. How many magnets did you use today?

However, there is more. The electron spin, which is the quantum mechanical origin of magnetism, can also be used to transport and process information in the form of spin currents or spin waves. This quickly developing technological field is called spintronics and emerged from discoveries in the 1980s concerning spin-dependent electron transport phenomena in solid-state devices. The Nobel Prize-winning discovery of giant magnetoresistance (GMR), and the related tunnelling magnetoresistance (TMR), have revolutionised hard disk drive and sensor technology due to the ability to detect minute magnetic field variations.

Discovering new magnetic materials and spintronics phenomena is a very active field of research nowadays, and high-performance computing has become an indispensable tool to accelerate this research. In this article, we highlight recent and ongoing contributions from our research groups in developing methods and tools for data- driven e-infrastructure to predict and compare commonly available experimental data for magnetic materials. This involves novel methods inspired by genetic algorithms (that are typically found in biological systems) being used to identify magnetic configurations, a method to simulate magnetisation dynamics where spin-lattice effects are included, multiscale modules in simulations, and the connection to ab-initio electronic structure theory based on density functional theory (DFT), as well as exploration of new computational architectures. (Walter Kohn shared the Nobel prize for chemistry in 1998 for his work on DFT.)

Ab-initio Theory of Exchange and Atomistic Spin-Dynamics

Simulations of magnetism rely on having a good estimate of the exchange- and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM) interactions of the material in question, in addition to dipolar energy and the magneto crystalline anisotropy. The dipolar interaction is a classical one, for which analytical expressions are known, while all other effects have their origin in quantum mechanics. For simulations on an atomistic level, where the magnetism is represented on the atomic scale, this implies that access to a microscopic spin- Hamiltonian (H) on atomic scale is needed. This normally involves the Heisenberg Hamiltonian for exchange, where the energy cost of rotating two magnetic moments is governed by a scalar number: the bilinear Heisenberg exchange parameter. In a more general form, this interaction is represented in matrix form, where the DM interaction is also present as an anisotropic, antisymmetric component. Due to seminal work in the middle of the 1980s, it is possible to directly calculate these interaction terms, via an expression that relies on the master equation of DFT, the Kohn-Sham equation. From the derivative of H with respect to the rotations of a magnetic moment, one can then calculate a local exchange-dominated field Bi as Bi = −dH/dmi that would provide a torque on the moment mi if it were to deviate from the orientation of Bi. Note that this is analogous to calculations of, for example, the force of an atom, if it were to deviate from its equilibrium position, via the expression Fi = −dE/dui, where E is the energy landscape generated by the positions, ui, of all atoms of the solid. This forms the basis for molecular dynamics simulations where, once the forces have been obtained, Newtonian mechanics is invoked to study the dynamics. In the field of magnetism, the situation is a bit more complex since mi is an angular momentum, which causes the dynamics of any deviation between Bi and mi to be expressed in terms of a torque. The resulting master equation of the dynamics is normally referred to as the Landau-Lifshitz or Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) equation and can be written as

dmi/dt = −γ mi × Bi − α (γ/mi) mi × [mi × Bi]

where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio and α is the Gilbert damping parameter. The first term of the LLG equation describes a conservative precession around the local magnetic field Bi, while the second term describes the dissipative motion of aligning the moment mi with Bi. In order to incorporate thermal effects into the equations of motion, a Langevin-based approach can be used where a temperature-dependent stochastic contribution bi is added to the local field, keeping the remaining parts of the LLG equation intact. The equations of motion can then be integrated with standard numerical integrators, for example, from the Runge-Kutta family.

Multiscale Simulations of Magnetism

Multiscale modelling is a powerful approach in computational physics and materials science that enables the seamless integration of simulations across different length and time scales, and it plays a particularly vital role in the study of spin dynamics. The core idea of multiscale methods is to bridge atomistic and continuum descriptions, each tailored to a specific scale, within a unified computational framework. This is crucial in magnetic systems, where microscopic interactions at the atomic level, such as exchange coupling, anisotropy, and Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction, determine macroscopic behaviours like domain wall motion or skyrmion dynamics. Thus, the atomistic spin dynamics region models individual atomic moments and their interactions using the LLG equation, allowing for the resolution of local fluctuations and thermal effects. Conversely, the micromagnetic model describes magnetisation as a continuous field, enabling the study of larger domains with a reduced computational cost. The interface between these regions is managed through a combination of padding atoms, finite-difference grid interpolation, and damping bands to prevent unphysical reflections of high-frequency spin waves. Coarse graining further smooths the transition by gradually adjusting the interaction range near the interface. The framework developed in this work supports simulations involving complex magnetic properties [1,2]. It reproduces key magnetic phenomena such as spin wave interference, domain wall pinning, and skyrmion robustness in the presence of defects. For instance, the double-slit experiment and the tetrahedral anisotropy cluster embedded in a hybrid domain revealed the interplay between wave-like and topological excitations. Analytical models validate the observed behaviours, underscoring the physical accuracy of the multiscale approach. The implementation is extensible, designed to operate efficiently on large systems, and is available within the UppASD [7] simulation suite. Overall, this multiscale framework not only deepens our understanding of magnetism across scales but also lays the groundwork for future developments, including adaptive interfaces and finite element discretisation, which promise even greater flexibility and fidelity in simulating real-world magnetic materials.

Ultrafast magnetisation dynamics — the ability to change the magnetisation in a material following excitation by a femtosecond laser pulse — has opened up exciting technological possibilities like all-optical magnetic switching, where data bits can be written using light instead of magnetic fields and terahertz-speed memory devices. However, describing what actually occurs in the material in light-driven transient magnetisation dynamics has turned out to be very complex. The electrons, spins and lattice motions interact in highly nontrivial ways. Thermodynamically, one can describe the interactions by introducing a temperature for each degree of freedom or reservoir (electrons, spins, and lattice) together with an interaction pathway between each of the reservoirs (for example, the electron-phonon interaction), leading to the so- called three-temperature model. By realising that the heat distributions of each reservoir should be calculated self-consistently, we have developed a method that describes the process much better than the conventional three-temperature model. We call our new method the heat-conserving three-temperature model (HC3TM) [3].

From Biology to Magnetism

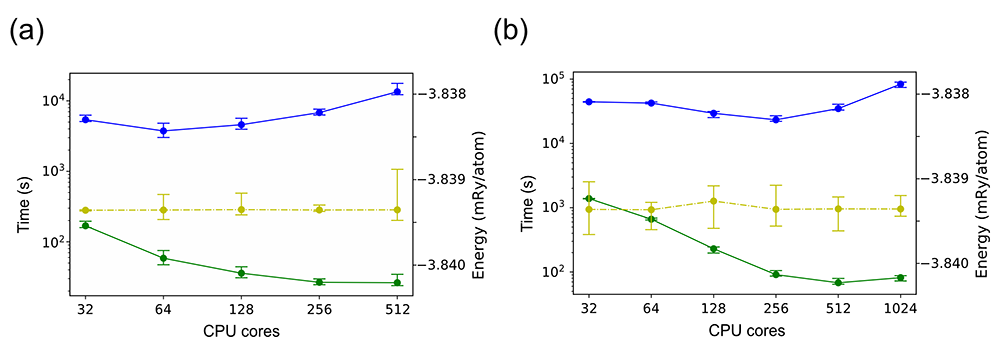

We have developed a novel optimisation technique inspired by genetic algorithms, called the Genetic Tunnelling Optimiser (GTO) [4]. This method efficiently locates global minimum energy states in complex magnetic systems by effectively navigating potential energy surfaces characterised by numerous local minima. Our approach achieves significant parallelism, allowing hundreds of independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) processes, each targeting local minima, to run concurrently. This parallel execution accelerates the main optimisation process. The figure below illustrates how the GTO method can effectively utilise the CPU nodes of the NAISS Dardel system at PDC for large-scale concurrent computations for two spin system sizes.

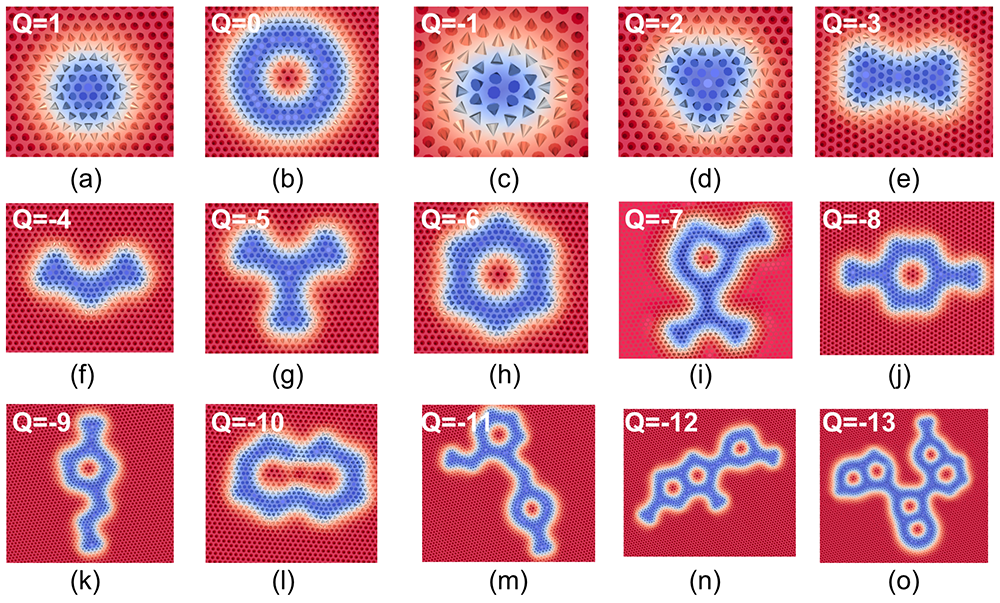

In order to discover long-lived, metastable spin textures, we utilise a neural-network- based approach. The method has successfully identified new skyrmionic metastable state spin configurations with high topological charges in Pd/Fe/Ir(111) [5]. By leveraging Dardel’s graphical processing unit (GPU) nodes with AMD MI-250X GPUs, researchers can now efficiently explore increasingly complex potential energy landscapes and accelerate discoveries for non- trivial spin textures. The figure on the next page shows a subset of identified topological metastable spin textures in the Pd/Fe/Ir(111) system in the presence of an external magnetic field with a strength of 3.5 Tesla.

To address the significant volumes of data produced by multiscale magnetic simulations, we have developed SpinView, an interactive visualisation tool designed for filtering, analysing, and presenting vector field data. SpinView enables rapid generation of high-quality publication-ready images, videos, or interactive web pages [6]. It seamlessly integrates with various spin dynamics simulation tools and efficiently manages the visualisation of large-scale long-time simulation trajectories directly within cloud-based workflows.

Turning to the GPU Architecture

The previously mentioned long-lived spin textures can range in size from nanometres to even micrometres, involving thousands to millions of atoms. Understanding how these structures behave over time – their dynamics – is also crucial for potential technological applications. The dynamics is often studied using atomistic spin dynamics simulations. To model systems at these large scales more efficiently, we have adapted our computational methods to run on GPUs. We are working on the development of GPU code backends for modelling magnetisation dynamics on microscopic length scales within the formalism of atomistic spin-dynamics (ASD) [7,8] and spin-lattice dynamics (SLD) [9]. The ASD formalism is a well- established method for ab initio modelling of magnetic material physics, enabling numerical simulations of the properties of magnetic materials. It provides theoreticians and experimental physicists with access to a wide range of physical observables, both for systems in thermal equilibrium and for systems driven out of equilibrium by thermal or electromagnetic pulses or other forms of excitation. The SLD formalism extends ASD by incorporating ionic displacement into the set of state variables, allowing for simultaneous modelling of lattice and spin dynamics.

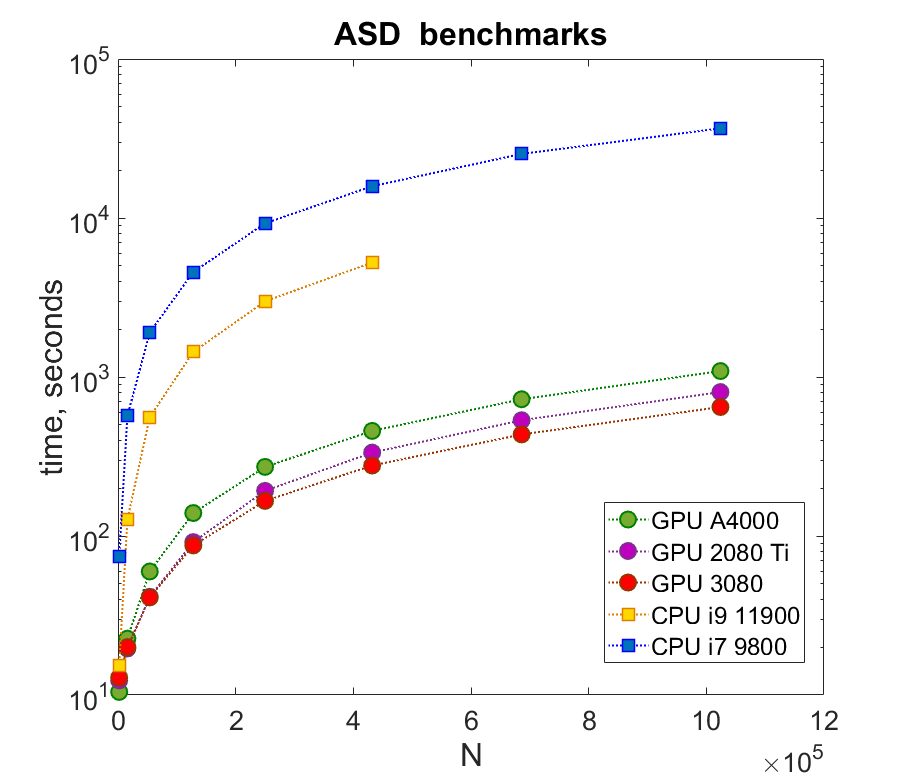

In the preliminary implementation, kernels for magnetic field calculation for bilinear spin-spin pair interaction and one numerical integrator have been implemented with the CUDA programming model for use on single NVIDIA GPUs. Benchmarks for the simulation of bulk body-centred cubic (bcc) Fe firmly establish the proposition of high speed-up for magnetisation dynamics simulation on GPU hardware. The results of these simulations are presented in the figure above for several widely available hardware devices.

While the performance of the code at a relatively small number of spins, N, is comparable across all the hardware, a steep increase in execution time is observed for both CPUs, with the i9-11900 significantly outperforming the i9-9800X. Despite both CPUs having relatively high clock speeds, they fall behind all the GPUs, even at moderate N values, due to the massive parallelism of the ASD algorithm. The difference in performance reaches a 60-fold speed-up between the slowest and fastest devices for N of the order of a million. In contrast, the difference in execution time between the GPUs is relatively less significant, with the RTX 3080 outperforming its competitors, likely due to its greater number of CUDA cores. The superior performance of the GPUs highlights the compatibility of spin-related problems with GPU architectures and points to the future direction for the increasingly computationally demanding field of magnetic simulations.

In order to be able to take on modelling on the same footing as magnetic and phononic degrees of freedom in solids, we have developed a method for coupled spin-lattice dynamics simulation [9]. The method is based on a coupling of atomistic spin dynamics and molecular dynamics simulations, expressed through a spin-lattice Hamiltonian, where the bilinear magnetic term is expanded up to second order in displacement. The motion of the atomic spins is described by the LLG equation and the ionic dynamics follow Newtonian dynamics.

A particular challenge for spin-lattice dynamics simulations is that the range of intrinsic and extrinsic system frequencies spans many orders of magnitude, with the consequence that the computational effort can become an order of magnitude larger than for a pure lattice or pure spin dynamics simulation of a system. Moreover, given that regular periodic boundary conditions violate the conservation of mechanical angular momentum, capabilities for the simulation of larger systems with open boundaries become of importance. Hence, we have identified the need for capability enhancement by means of implementing a GPU backend for SLD.

Conclusion and Outlook

Magnetic materials are essential for future sustainable technological development and are widely used in every aspect of our everyday lives, ranging from magnetic memories to wind power plants. To accurately describe experimental observations and predict magnetic properties for various applications, one needs to perform extensive simulations across different time and length scales. Many magnetic phenomena (such as ultrafast demagnetisation) need to take lattice dynamics into account in addition to the study of magnetic systems, or it may be necessary to consider the dynamics of millions of atoms to predict the behaviour of non-trivial magnetic textures, which are an integral part of prospective spintronic devices.

Multiple powerful approaches have been recently proposed in our groups to describe various magnetic phenomena, such as coupled atomistic spin-dynamics simulations, neural network-based algorithms for searching for metastable spin textures, and a framework for multiscale modelling to bridge atomistic and continuum descriptions. These developments facilitate a deeper understanding of various magnetic effects and result in good agreement with experimental observations, such as the robustness of skyrmions in the presence of defects, timescales of ultrafast magnetisation dynamics of ferro- and antiferromagnets, and many others. To improve computational efficiency and data treatment for those resource-hungry simulations, we have recently proposed optimisation techniques enabling faster and more efficient simulations leveraging existing GPU nodes. The development of the SpinView software expedites the fast treatment of a large amount of data from magnetic simulations. Proposed methods and optimisation techniques provide a strong basis for further progress in magnetism and materials science research.

References

- N. Salehi et al., “Micromagnetic-atomistic hybrid modeling of defect-induced magnetization dynamics”, preprint arXiv:2504.14019 (2025).

- E. Méndez et al., “A multiscale approach for magnetization dynamics: Unraveling exotic magnetic states of matter, Phys. Rev. Research 2, 013092 (2020).

- M. Pankratova et al. “Heat-conserving three-temperature model for ultrafast demagnetization in nickel”, Phys. Rev. B 106, 174407 (2022).

- Q. Xu et al., “Genetic-tunneling driven energy optimizer for spin systems”, Comm. Phys. 6, 239 (2023).

- Q. Xu et al., “Metaheuristic conditional neural network for harvesting skyrmionic metastable states”, Phys. Rev. Research 5, 043199 (2023).

- Q. Xu et al., “SpinView: General Interactive Visual Analysis Tool for Multiscale Computational Magnetism”, preprint arXiv:2309.17367 (2023).

- UppASD code github.com/UppASD/UppASD

- O. Eriksson et al., “Atomistic spin-dynamics: foundations and applications,”, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, (2017).

- J. Hellsvik et al., “General method for atomistic spin-lattice dynamics with first-principles accuracy”, Phys. Rev. B 99, 104302 (2019).